WHY SINASOS IS UNIQUE?

It was due to a handful of foresighted Sinasites, less than one thousand out of 2 million people immigrating, that photographs and stories of Sinasos exist, and contribute to the preservation of the village.

Villagers have long produced apricots, walnuts, apples, opium, wheat, and grapes for their own consumption, but they needed a cash income as well. To provide this, as early as the 17th century village men would travel to Istanbul to work as seasonal workers. Their success eventually provided Sinasites (those who lived in Sinasos, now Mustafapaşa) the privilege of urbanized life.

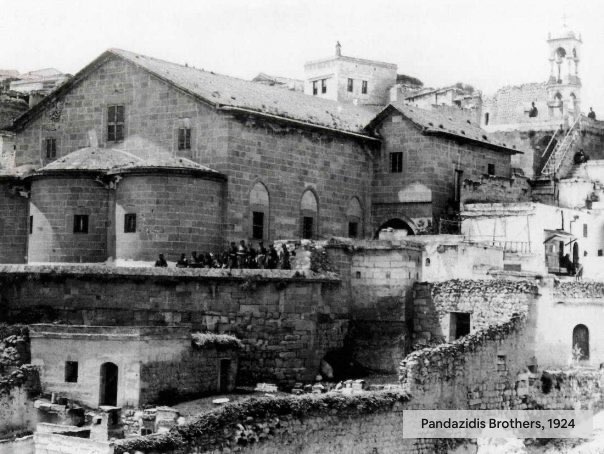

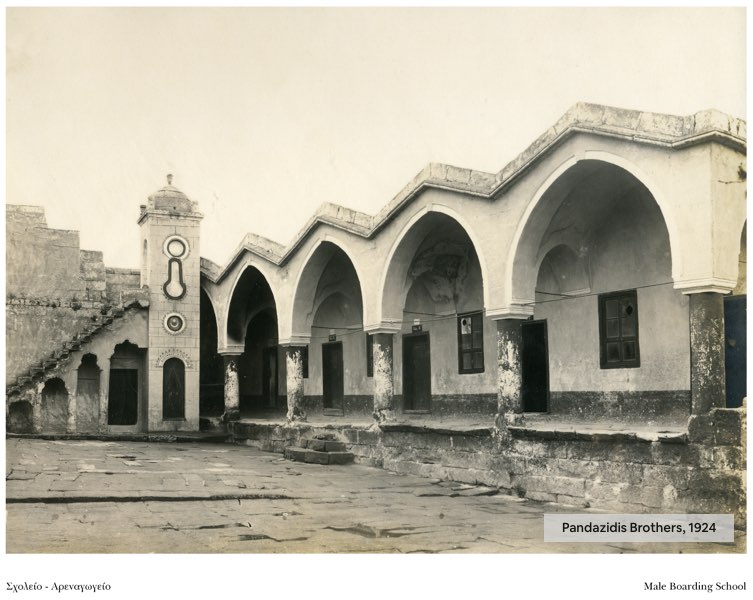

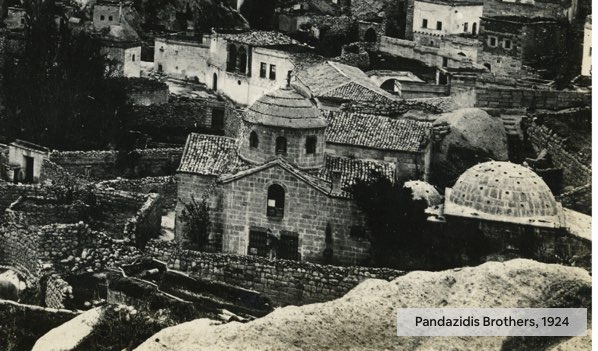

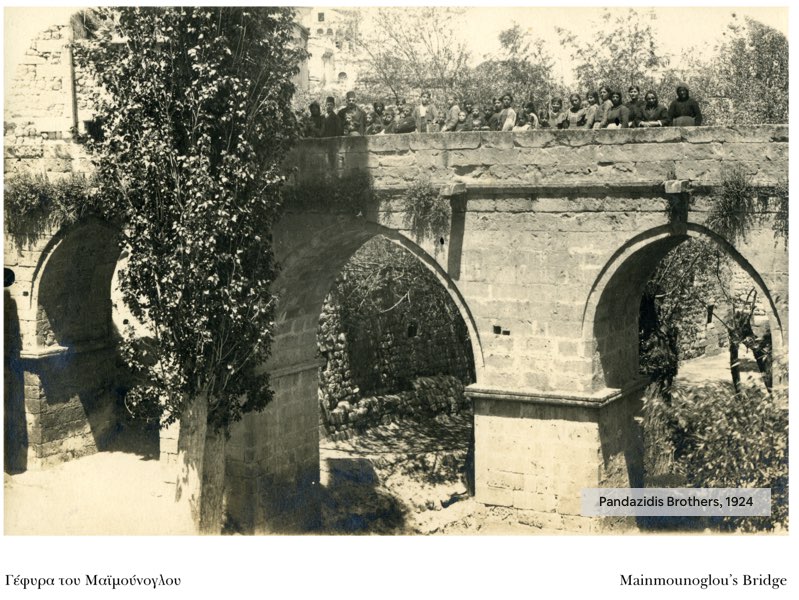

During their early years in Istanbul, these men worked as oil millers, producing linseed and sesame seed oil, along with working as fishmongers in shops. Eventually, they developed their trade and established the Guild of Caviar Merchants, monopolizing the dried fish, fish roe, and caviar market of the Ottoman Empire. As faster steam-powered ships came into service, the Sinasites exported caviar as far away as Paris! Success in this trade increased their confidence, and they pushed into other enterprises such as becoming the sole supplier of materials and food to ships that passed through the Bosphorus Strait in Istanbul. Back home, they generously invested in Sinasos by building stately mansions, public buildings, baths, caravanserais, churches, and schools. Thus, this rural village of Sinasos developed an urbanized lifestyle in the heart of Cappadocia! During the heyday of the village, the population numbered 4,500 Greeks (including the Turkish-speaking Anatolian Greeks called Karamanlides), as well as 1,500 Turks.

Independence War of the Turks followed WWI, and the Lausanne Treaty dated 1923 put an end to it. This treaty enforced the exchange of populations, minorities between Greece and the newly founded Turkish Republic.

Roughly 2 million people immigrated as a result. When the Sinasites received the decree imposing them to immigrate, they did an astonishing thing! Fearing that they would be looked down upon as refugees, they decided to document their life and home-town to have proof of their standards and privileges. For this, they hired two photographers to visually document their hometown and in the meantime wrote all they can about their life. While immigrating through Istanbul, they left the photo plates and manuscripts at the safekeeping of a Greek doctor who would later collect them all in an album.

Turks who came from Jerveni village of Kastoria of Greece replaced them.

It was due to a handful of foresighted Sinasites, less than one thousand out of 2 million people immigrating, that photographs and stories of Sinasos exist, and contribute to the preservation of the village.

Sometimes visitors ask us how we knew what the houses looked like. Easy to answer, we have photos!